|

| Anita Nahal |

-Anita Nahal

Background:

I grew up in the

previous century, mostly in India with a lavish sprinkle of travels to varied

countries in Europe, Africa, and the Americas, and a stay for a few years in

the US in my childhood plus some time spent there later doing my Ph.D. and

Fulbright Post-Doc Scholar-in-Residence prior to moving to America permanently

in 2002 with my then teenager son. Stree-Shakti and Insaan-Shakti were

ingrained in me by broadminded parents, by the diverse societies we visited and

resided in, and by the gift of motherhood bestowed on me by God and destiny. Blessings

were and are manifold. Furthermore, Hinduism with its hundreds of female, male

and androgynous Gods and Goddesses suggests a very liberal way of manifesting

and living. The plausibility of choice, the freedom to worship whom we wish, in

the manner we wish, without strict rules allows for a wide range of

possibilities in transcribing these cultural/religious traits into our daily

lives. I believe learning is passed on generation to generation through an

amalgam of traditions, religion, culture, oral history, and the written word,

plus lived experiences.

Many elements of

an individual’s identity and socialization are molded by a set of circles from

the minutest and most intimate family to society, the nation, and the largest,

most esoteric, emotionally distanced, yet in some ways most immediate spectrum

being humanity’s cautionary loop. These circles function at times,

independently, and at other times in conjunction with each other, lapping and

overlapping in a plethora of resemblances to John Venn’s diagram. Despite their

ability to think, speak, read, and write in a way that has assisted humans to

advance more than other species on this planet, yet this very competence has curdled

some to be over-competitive, jealous, mean, and self-indulgent. In this

increasingly dystopian scenario, where we have yet to reach, I believe, that

tipping point as Morton M. Grodzins, American Political Scientist had

enunciated, I was raised by parents who had a heightened, progressive,

futuristic genderist philosophy.

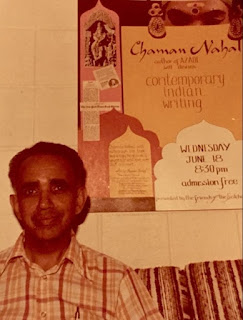

Papa in a library in the US.

Location unknown. Sometime in the 1980s

On numerous

occasions, I heard my grandparents pray out loud in family gatherings for the

boon of a son to my parents. Besides the male factor, I also grew around aunts,

uncles, cousins, and friends who lamented about my dark skin. Added to the

repetitively voiced familial and societal opinions, fear and claustrophobia over

women’s idolization, pedestalization, sexualization and violence, imagined and

re-imagined by Bollywood and Indian television melodramas also pilled on,

inculcating in me repulsion for and rejection of such patriarchal norms. My

parents aided me in this philosophy as both rejected family pressures and

Bollywood/television typecasting and insisted that men and women are equal, that

I was no different, “no less than a son,” and that skin color had no impact on human

intelligence or success as did no other differentiations artificially crafted

by some humans. They were Arya Samajis and rejected the caste system and

the ostentatious application of humans conduct. As a young impressionist girl

these views held the potential of personal growth in a liberated environment. I

was also by nature a precocious child with a deep organic desire to expose

injustice and take up cudgels for the underdog, something that led me to “burn

my fingers” as the expression goes, many times.

And so came the knowledge:

Learning by example, through sharing of family stories, and through formal education were imperative elements in my growth. Besides the basic three Rs, finding the definitions of two new words each day, reciting a memorized poem per week, analyzing new books, articles in magazines or happenings around the globe were routine. When I signaled my interest to do a bachelors in law after high school, my parents without any fanfare said, okay sure, we can talk about it after you complete your masters! Later pursuing an M.Phil. and Ph.D., was a given considering both my parents were doctorates.

My father,

Professor Late Chaman Nahal taught in the English Department at Delhi

University and was also a writer. His and my mother’s families (unknown to each

other at the time) fled the new Pakistan during partition in 1947 and moved to the

new India. As refugees, both families, like thousands of others, tried to find

a substantial sense of roots or create new ones to formulate a semblance of

normalcy in the new era the division of the land brought the South Asians. My

father poured a lot of his emotions and feelings into his creative writings,

ultimately publishing over twenty books.

|

| Papa at an event about his writings in the US. Year: Most likely, 1975 |

From his spirit of humanity and general forgiveness despite having lost his sister, her husband, and their unborn child in a train massacre on their way to India during partition, I learned compassion, fairness, and balance. And seeing him write, in addition to my own stances on injustice, enthused in me a burning desire to scribble as well from as early an age as nine. Consequently, I also imbibed from him writing skills, patience for the complex vagaries of publication, and moving on when rejection letters sat stoically in mailboxes. He was also a critique of bewildering gender expectations and couldn’t comprehend why only when women must keep the Karva Chauth vrath* and insisted on keeping a fast along with my mother.

Mummy with the Delhi State Teachers Award.

Year: Most likely between 1985-87

My mother, Late Dr.

Sudarshna Nahal was principal of Satbhrawan Arya Samaj Girls Senior Secondary

School in Delhi. An amazing human being with one of the kindest natures I have

ever known, she became my role model in a different way than my father.

Somehow, again organically, I was taking it all in. I would visit her school

and observe the way she conducted herself, the way she interacted with

students, faculty and staff, the way she was steadfast, the way she had a

genuine heart to help others and the way she walked and talked, the way she sat

with warmth and determination in the principal’s chair. Above all, this

instilled in me leadership skills and I realized that I was very similar to my

mother and carried her enterprising, courageous, daring, go-getter, survivor

attitude and aura as my badge of honor throughout my life.

I also learned from my mother how to run after, and for, one’s dreams. One of hers was to raise funding for tuition for students whose families could not pay, for the school labs and classrooms, for the library and for the building. To achieve this, she went to the top leadership in the country and met with prime ministers of India to seek funds for her school. They visited her school, or she went to the Prime Minister’s residence. What confidence, fearlessness, and belief in her convictions she had!

Mummy at Teen Murti House, New Delhi above with

then Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru. Year: Most likely, 1962

Mummy when she visited Lal Bahadur Shastri, PM

of India. Year: Most likely between 1964-66

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi during her visit to

mummy’s school. Year: Most likely 1966-1967

Now a legacy to pass on:

Therefore, both my father and mother ecnouraged in me a keen awareness of my identity and role in life (not just in society or family), and an intential effort to improve myself, to be a better version each day. The best way I can honor them is to ensure that I pass on all I have learned to my son and to others. Writing seems hereditary in our family as my son writes beautifully. When we left India in 2002, he was the student editor of the children’s section of The Hindustan Times. While professional work takes up much of his time these days, yet, he used to write poetry, humor pieces, travel, envrionment and everyday life articles with aplomb.

Stree

Shakti is not a given because I am a woman. Nothing in life is a

given. Everything, each and every particle of our making, is to be striven for,

worked for, and earned. Also, I don’t like to place myself within any box, in

fact I don’t believe in boxes. Women, LGBTQ+ or men, we all are humans and as I

said in the beginning, I ascribe to Insaan-Shakti (Human power), or Insaniyat

(Humanity). For me huamnism stumps feminism. It does not imply I don’t strive for

rights that are specific to women. Yet, at the same time I wish to ensure that when

we struggle for women’s rights, we understand and perpetuate that we are also

striving for human rights. And Shakti is to be benevolent, not harmful.

It is to be for the benefit of others and humanity in general, not for some. As

American writer, Patricia Cornwell said, “I believe the root of all evil is

abuse of power.[1]

I

shall end with a poem of mine from my second book of poetry, Hey-Spilt Milk

Is Spilt, Nothing Else (Authorspress, 2018) which was my mother’s favorite

when I first wrote it though she and my father didn’t live to see this and my later

published books.

Lone voice

Woman, woman

Shy not, say it

Uphold dignity

Even if ceaselessly

The darkened mushroom clouds

Threaten an acid rain.

Glossary:

*Karva Chauth Vrath: A Hindu tradition wherein married women observe a fast without water or food for one day for the longevity of their husbands. Unmarried women can also keep the fast to get a “good” husband.

*Insaniyat: Humanity

*Shakti: Power

*Stree-Shakti: Women power

No comments :

Post a Comment

We welcome your comments related to the article and the topic being discussed. We expect the comments to be courteous, and respectful of the author and other commenters. Setu reserves the right to moderate, remove or reject comments that contain foul language, insult, hatred, personal information or indicate bad intention. The views expressed in comments reflect those of the commenter, not the official views of the Setu editorial board. प्रकाशित रचना से सम्बंधित शालीन सम्वाद का स्वागत है।